Ion source development

IR-LAAPPI

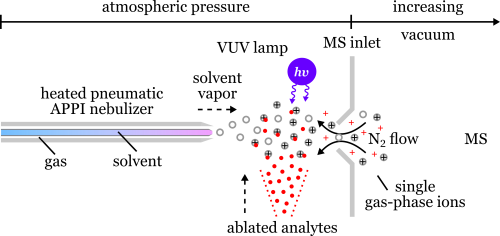

Infrared laser ablation atmospheric pressure photoionisation IR-LAAPPI is based on atmospheric pressure photoionisation APPI, which is a soft ionisation method operating at atmospheric pressure and suitable for a wide range of molecules regardless of their polarity (cf. ESI in IR-LAESI). In addition to the IR laser source, the IR-LAAPPI source consists of a heated pneumatic nebuliser and a vacuum ultraviolet VUV light source emitting 10-eV photons. The first IR-LAAPPI studies utilised in-house fabricated microchips as APPI nebulisers, which were later replaced with a DESI-like pneumatic sprayer, making IR-LAAPPI more accessible to other research groups. The APPI nebulisers vaporise the spray solvent that is typically pumped with a flow rate of 0.5−10 μL/min. The hot solvent vapor of 200–400 °C meets the ablated neutral analytes in the gas-phase, above the sample, while the emitted VUV photons can initiate the ionisation. As the APPI ionisation process occurs solely in the gas phase, it is typically less susceptible to ion suppression than ESI, especially in measurements of analytes from biological matrices.

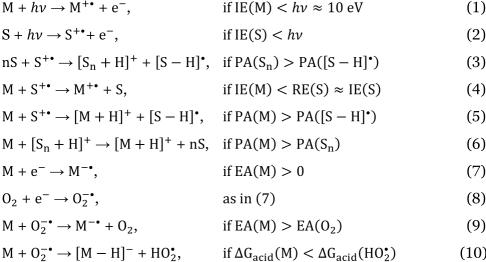

APPI ionises molecules either by a charge exchange or a proton transfer reaction and it mainly produces molecular ions and protonated/deprotonated molecules although various other reaction pathways are also feasible. The ionisation of analytes through charge exchange allows IR-LAAPPI to be used for the analysis of less polar molecules than IR-LAESI, and different APPI-based methods have been often applied for the analysis of a wide range of less polar compounds such as steroids, ceramides and polyaromatic hydrocarbons PAHs that are challenging to ionise with ESI. In addition, APPI does not typically produce alkali metal adduct ions, which simplifies the IR-LAAPPI mass spectra of biological samples. However, the level of fragmentation with APPI is slightly higher than with ESI due to the resulting analyte ions having a larger amount of excess internal energy. The fragmentation is often observed as a loss of water molecules, especially with steroids. Unlike ESI, APPI cannot produce multiply charged ions of large biomolecules, which limits the use of IR-LAAPPI to the analysis of 50−2000 Da compounds. The ionisation mechanisms in IR-LAAPPI are likely to follow similar reactions (Reactions 1−9) as in APPI. In theory, APPI can directly ionise a wide-range of analytes M, as most organic compounds have ionisation energies IEs of 7–10 eV, which are smaller than the energy of the emitted photons (Reaction 1). However, direct APPI of an analyte is a statistically unlikely event due to the low analyte–to–solvent ratio. The ionisation efficiency of APPI is often enhanced with the use of solvents S that have IEs below 10 eV (i.e., dopants) and can thus be ionised by direct APPI. Commonly used APPI solvents include acetone IE = 9.7 eV, toluene IE = 8.8 eV, chlorobenzene IE = 9.1 eV, and anisole IE = 8.2 eV, which can act as a primary reagent and form molecular ions (Reaction 2).

Overall, the ionisation mechanisms in APPI are complex. In positive ion mode, if the IE of the analyte is smaller than the recombination energy RE of the solvent, the analyte can form radical cations by a charge exchange reaction with the solvent ion (S+•, Reaction 4). The solvent ion S+• can also donate a proton to the analyte by a proton transfer reaction (Reaction 5) if the proton affinity PA of the analyte is higher than the resulting deprotonated solvent radical [S − H]•. Moreover, protonated solvent clusters ([Sn + H]+, Reaction 3) can also ionise the analyte through proton transfer (Reaction 6) if the PA of the analyte is higher than that of the solvent cluster Sn. As such, proton transfer and charge exchange are competing reaction pathways in APPI, and in some cases, one can dominate the other. For example, if the PA of the solvent is high, such as with acetone PA = 812 kJ/mol, self-protonation can take place (as in Reaction 3) and lead to the formation of mainly protonated analytes. In negative ion APPI, if the electron affinity EA of the analyte is positive, it can ionise through an electron capture reaction with the thermal electrons that are produced in the photoionisation of the solvent or at the metal surfaces of the ion source (Reaction 7). On the other hand, atmospheric oxygen with high EA can also capture the thermal electrons and produce superoxide ions (O2−•, Reaction 8) that can consecutively react with the analytes either through charge exchange (Reaction 9) or proton transfer (Reaction 10) depending on the EA or the gas-phase acidity \(\Delta G_{acid}\) of the analyte, respectively. In addition to Reactions 7−10, various other reactions such as substitution, fragmentation, oxidation, and anion attachment can also occur in negative ion mode.

IR-LAESI

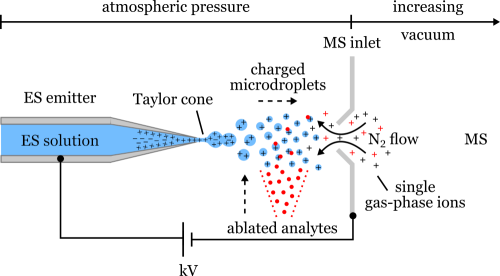

Infrared laser ablation electrospray ionisation IR-LAESI based on electrospray ionisation ESI, which a soft MS ionisation method operating at atmospheric pressure and suitable for a wide range of polar and medium–polar analytes with minimal fragmentation. IR-LAESI typically utilise tapered 50–100 μm ID stainless-steel electrospray ES emitter capillaries for producing microdroplets with an excess charge at their surface. The microdroplets are formed solely with the use of a high voltage that generates an electric field between the tip of the ES emitter and the inlet of a mass spectrometer, which leads to charge accumulation in the pumped solvent at the tip of the emitter capillary. The ES emitter position affects the set high voltage that must be precisely applied to produce a stable Taylor cone at the tip of the ES emitter capillary, from which the charged microdroplets burst away via coulomb repulsion. The formation of a so-called cone-jet spray mode is often observed via a microscope camera, while the onset voltage \(V_{onset}\) for successful ESI operation can be approximated with Equation (1):

\[ V_{onset} = 2 \times 10^5 \times \sqrt{\gamma \times r_c} \times \ln \left( { {4 \times d} \over {r_c} } \right) \tag{1}\]

where \(r_c\) is the outer radius of the emitter capillary, \(d\) is the distance between the emitter and the MS inlet, and \(\gamma\) is the surface tension of the solvent.

The presented ESI device is typically used with 0.2–2 μL/min flow rates and is often called pure ESI to differentiate it from the pneumatically assisted emitters that are widely used in mL/min flow rate applications such as liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry LC-MS. This ESI device can also be considered to be an electrochemical cell that consists of an electrode (ES emitter), a planar counter electrode (MS inlet), and a pumped electrolyte (ES solution), and it can thus ionise analytes also through electrochemical oxidation or reduction. As such, the operation of ES post-ionisation depends on an electrically conductive solvent or solution such as water, MeOH, or ACN, or their mixtures. Furthermore, an acid or a base is often added to the ES solvent to act as a proton donor or acceptor and thus to increase the formation of protonated or deprotonated molecules. ESI allows the formation of gas-phase ions from the ablated analytes in the gas-phase and efficient ionisation of a wide-range of polar and medium–polar analytes with minimal fragmentation. ESI can produce protonated [M+H]+ and deprotonated [M–H]– molecules, different alkali metal and halogen adduct ions such as [M+Na]+, [M+K]+, and [M+Cl]–, and multiply charged ions of large molecules, such as peptides, proteins and polymers. The formation of multiply charged ions allows the analysis of large >100 kDa molecules with mass analysers that have an upper mass limit of a few thousand m/z. The capability of ESI for macromolecular analysis at atmospheric pressure has been largely inaccessible by other MS ionisation methods such as APPI in LAAPPI.

SX-APPI

Soft X-ray atmospheric pressure photoionisation SX-APPI is a recently developed ionisation technique for liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry LC-MS. The SX-APPI source emits 4.9 keV photons to displace a valence electron and often inner shell electrons from LC eluents and atmospheric gases, initiating an efficient ionisation process, particularly in the negative ion mode. SX-APPI does not require a dopant to achieve high ionisation efficiency, unlike traditional vacuum ultraviolet APPI VUV-APPI with 10-eV photons. This allows the use of existing LC methods developed for ESI-LC-MS analysis, making SX-APPI a convenient choice for acquiring complementary chemical information.

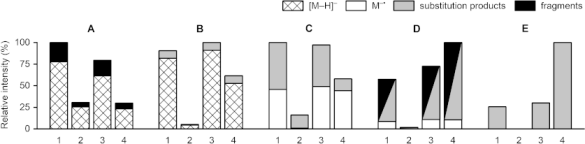

SX-APPI has the main advantages of traditional VUV-APPI, such as the ability to efficiently ionise non-polar compounds via the formation of radical ions. The advantage of SX-APPI for the analysis of non-polar compounds is presented in the figure below. The figure clearly shows that the dopant-free SX-APPI provides better or similar sensitivity to traditional doped VUV-APPI in the analysis of non-polar compounds with different functional groups.

In SX-APPI, the primary electrons produced in the ionisation process are rapidly thermalised close to 0 eV and can be captured by the molecules with positive EAs. Since oxygen EA = 0.451 eV is present in the SX-APPI source in much higher concentrations than the analyte molecules, it is evident that oxygen is first ionised to superoxide ions O2−•, similar to the situation in VUV-APPI (Reaction 8). In the gas phase, O2−• is a relatively strong base and can react directly with an analyte M by a proton transfer reaction, producing deprotonated molecules [M−H]− (Reaction 10). In addition, O2−• can initiate the formation of deprotonated solvent molecules, which in turn can deprotonate an analyte if the gas-phase acidity of the analyte exceeds the acidity of the solvent molecule, i.e., if the \(\Delta G_{acid}(M)\) is lower than the \(\Delta G_{acid}(solvent)\). Charge-exchange reactions in the negative ion mode are possible if an analyte M has a higher EA than that of a reactant molecule (Reaction 9).

Literature

All the information on this page is based on the following articles. Please read them for further information and references to the original research articles.

- Hieta et al. A Simple Method for Improving the Spatial Resolution in Infrared Laser Ablation Mass Spectrometry Imaging, 2017, Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, https://doi.org/10.1007/s13361-016-1578-7c

- Hieta et al. Sub-100 μm Spatial Resolution Ambient Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Rodent Brain with Laser Ablation Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (LAAPPI) and Laser Ablation Electrospray Ionization (LAESI), 2020, Analytical Chemistry, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.0c01597

- Hieta et al. Soft X-ray Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization in Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry, 2021, Analytical Chemistry, https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.analchem.1c01127

- Hieta et al. Mass Spectrometry Imaging of Arabidopsis thaliana Leaves at the Single-Cell Level by Infrared Laser Ablation Atmospheric Pressure Photoionization (LAAPPI), 2021, Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry, https://doi.org/10.1021/jasms.1c00295

- Hieta. Development of Infrared Laser Ablation Based Ambient Mass Spectrometry Imaging Methods, 2022, University of Helsinki, Doctoral dissertation, http://hdl.handle.net/10138/346769